|

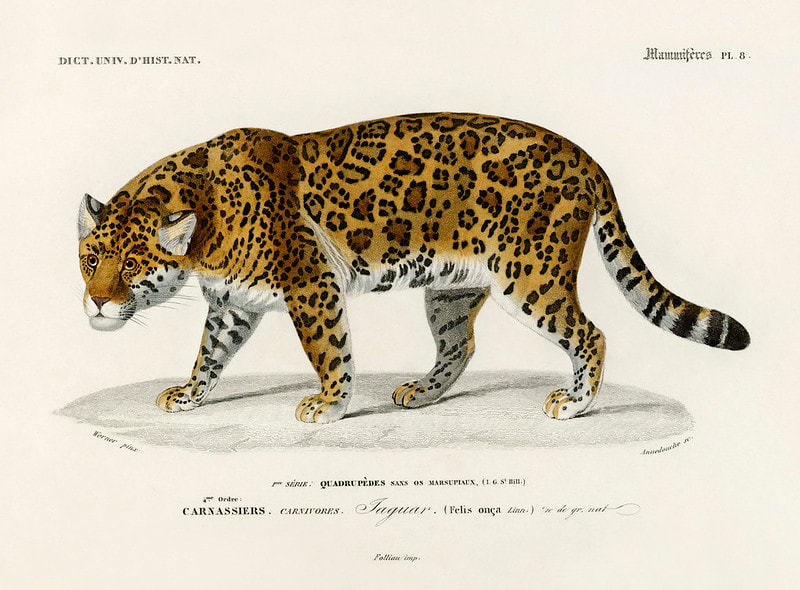

Did you know that North America once had a widespread and thriving population of jaguars, or "leopards," as the first European colonists called them? In my research for Weroansqua, I have come across several references to large spotted cats in Virginia and North Carolina as late as the 1700s.

The explorer Johann Lederer, who traveled in 1670 from present-day Petersburg, Virginia westward to the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains and then south into the North Carolina piedmont before returning to Virginia along the coastal plain, wrote that, "The Highlands [Piedmont] . . . [are] over-grown with underwood in many places, and that so perplext and interwoven with Vines, that who travels here, must sometimes cut through his way. These Thickets harbour all sorts of beasts of prey, as Wolves, Panthers, Leopards, Lions, &c . . . ." and, "Small Leopards I have seen in the Woods, but never any Lions, though their skins are much worn by Indians." (The Discoveries of John Lederer. 1672. Sir William Talbot, trans.) Earlier, William Stratchey, one of the Jamestown colonists, had observed the treasure house of Chief Powhatan and noted, "At the corners of this house stand four images . . . . set as careful sentinals (forsooth) to defend and protect the house (for so they believe of them): one is like a dragon, another like a bear, the third like a leopard, and the fourth a giant-like man, all made evil favored enough according to their best workmanship." (The Historie of Travaile into Virginia Britannia. 1612.) While the exact origin of the dragon or the giant-like man are difficult to pin down, the bear and the "leopard" were not creatures of legend to the Powhatan peoples; they were fearsome predators of the forest, known and sometimes hunted. John Lawson, a surveyor-general of North Carolina who traveled widely throughout the colony in the early 1700s, described one large wild cat as a "tyger." He explained that,"Tygers are never met withal in the Settlement; but are more to the Westward, and are not numerous on this Side the Chain of Mountains. I once saw one, that was larger that a Panther, and seem'd to be a very bold Creature. The Indians that hunt in those Quarters, say, they are seldom met withal. It seems to differ from the Tyger of Asia and Africa." (A New Voyage to Carolina. 1709.) From Lawson's account, we also hear the first suggestion that habitat loss may have contributed to the disappearance of the jaguar in the East: "never met withal in the Settlement." However, jaguars hung on in the Southwest into the 20th century, but were believed extinct there since the 1960s. Then a few intrepid jaguars made the difficult journey north from Mexico, starting in the late 1990s. Today, efforts are being made to repopulate the jaguar in the wildest parts of the Southwest, though not without debate regarding the jaguar's rightful claim to US soil.

0 Comments

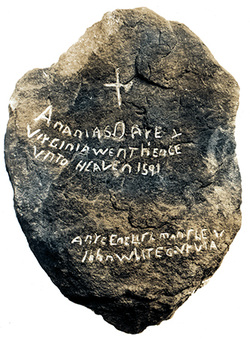

My first script, Dare to Follow, is currently being rewritten and updated into a novel, Weroansqua, that tells the story of Eleanor Dare and the Native peoples of North Carolina in much greater detail. I am convinced that Eleanor was an extraordinary young woman who possessed, like her artist father, John White, a deep curiosity about the world around her. The gradual dissolution of her colony, the Roanoke Colony, would have pushed her to explore and understand the Chowanoke people in whose territory -- and by whose grace -- she existed.

Eleanor represents an unusual direction in colonial America, a chance to imagine an America evolving from a place of understanding and cooperation between the races, rather than exploitation by white colonists. In Weroansqua, what is "lost" by the survivors of the Lost Colony is their exclusive Englishness; what is gained is an expanded humanity. Even in the traumatic wake of a massacre, Eleanor never lost faith in her true friends, the Chowanoke "savages," as she identified them for "any Englishman" who might read her account. In fact, she placed the hope of the remaining colonists in their hands. And if the stories of Native peoples are true, as I believe they are, then Eleanor's hope was not in vain, and her people lived. In graphic detail, the Normans show us their version of claiming the English throne: an Anglo-Saxon woman, most likely a mother and wife, clings to a child with one hand and reaches out pleadingly toward the Norman soldiers who are setting her home on fire. All to no avail, as the house burning is merely a precursor to the decisive battle at Hastings in 1066. Notice how much smaller she is than the Norman males surrounding her. The loss would not stop there. With the defeat of the Anglo-Saxon army, William of Normandy would claim the throne -- and much, much more. He and his Norman successors would take even the very Anglo-Saxon words for "wife," "woman," and "female servant," and shift them sharply to the left, putting this Anglo-Saxon "woman" -- and all her sisters -- firmly in the grip of their Norman overlords.

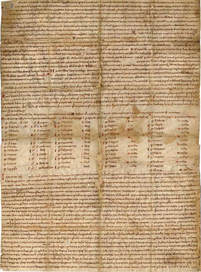

Early Anglo-Saxons used the word cwene for a married woman in general. During the nearly 500 years that the Anglo-Saxons controlled England, the word migrated to mean the wife of a noble, including the king. Yet even as cwene became more like the "queen" we know today, wif remained the generic term for "woman, female." In some verb forms, wif did have the meaning of "female taken in marriage," but with the growing usage of husbonda, or "master of the house," and husbonde, "mistress of the house," the distinct status of an ordinary married woman was preserved in the language. Such fine distinctions, however, as the feminine ending "e" instead of the masculine "a," were too similar for the Normans to bother to distinguish. Easier by far to grab a word that the Anglo-Saxons never used for free females, and apply it to all Anglo-Saxon females in general. Thus, wifman, a word used only for female servants (and slaves) was corrupted into "woman," et voila, every Anglo-Saxon female became no better than a servant -- available for sexual exploitation in the eyes of their Norman male rulers. This shift left "wife" free to take the place of cwene and husbonde. Again, the meaning was clear, and ominous: A "wife" was merely an Anglo-Saxon man's "woman," even though the Church still recognized (and blessed) the union. With the Church throughout England firmly in Norman hands, Anglo-Saxon "women" could expect no protection there. Married or single, high-b0rn or low, every female of the conquered English had to fear the predations of the Normans. And forever more, their language -- our language -- has enshrined that conquest of female identity. Aelfgifa of Northampton, as she is called in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, was part of a powerful and wealthy Mercian family in 1004 C.E. That was the fateful year King Aethelred gave a charter to Burton Abbey, founded by her uncle, Abbot Wulfric "Spot." In this charter, the king confirmed Wulfric's will, in which Wulfric endowed the abbey with rich estates throughout Mercia, and gave considerable property in Northumbria to his brother, Earl Aelfhelm -- Aelfgifa's father. Aelfhelm, his son Wulfgeat, his son-in-law Morcar, and the Archbishop of Canterbury, Aelfric, are among the witnesses to this charter.  Blinding. Maciejowski Bible, leaf 15, c. 1250. Source: medievaltymes.com Blinding. Maciejowski Bible, leaf 15, c. 1250. Source: medievaltymes.com The charter is well known. Seldom noticed, however, are the named guardians of the bequests in the charter. Nearing death, Abbot Wulfric puts the security of his family's earthly riches in the hands of just three men -- Aelfhelm, his brother; Archbishop Aelfric, his religious superior; and Aethelred II, his king. Two years later, only one of these men would still be alive. In 1005, Wulfrun, mother of Abbot Wulfric and Earl Aelfhelm, and matriarch of her family, dies after a long and full life. A descendant of King Aelfred the Great, her own personal wealth and status may have protected her as long as she lived. However, another death in the same year strips any remaining protection from Wulfrun's family. On November 16, Archbishop Aelfric of Canterbury dies. Now only Earl Aelfhelm and King Aethelred remain as guardians of the vast estates which Wulfric, and presumably Wulfrun, have left behind in Mercia and Northumbria. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle entry for the year 1006 describes what happened next: This year . . . Wulfeah and Ufgeat were deprived of sight; Ealdorman [Earl] Aelfhelm was slain. John of Worcester's Chronicon ex Chronicis provides additional details: The crafty and treacherous Eadric Streona, plotting to deceive the noble Ealdorman Aelfhelm, prepared a great feast for him at Shrewsbury . . . But on the third or fourth day of the feast, when an ambush had been prepared, he [Eadric] took him into the wood to hunt. When all were busy with the hunt, one Godwine Porthund, a Shrewsbury butcher, whom Eadric had dazzled long before with great gifts and many promises . . . suddenly leapt out from the ambush, and execrably slew the ealdorman Aelfhelm. After a short space of time, his sons, Wulfheah and Ufegeat, were blinded, at King Aethelred's command, at Cookham, where he himself [the king] was staying. Much has been written about the violence and treachery of Eadric Streona. In simple terms, he was King Aethelred's enforcer. Yet even he refuses, this time, to do the dirty work himself, and hires a local butcher to kill Aelfhelm. Not satisfied with murdering the father, King Aethelred then orders both of Aelfhelm's sons, Wulfheah, who witnessed the charter, and his younger brother, Ufegeat, to be blinded in his presence. Since a blind man cannot inherit property in Anglo-Saxon England, this vicious act immediately removes the claims Wulfheah and Ufegeat have on their father's lands.

Now no man stands between King Aethelred and the rich estates given to Aelfhelm and to Burton Abbey. Again, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle sums up the outcome: "A.D. 1007. In this year also was Eadric appointed Ealdorman over all the kingdom of the Mercians." The king's man has his reward, for past and future services. Burton Abbey, on the other hand, declines from a richly endowed religious house to one of the poorest abbeys in England. And Northumbria? King Aethelred appoints a man named Uhtred to be its new earl. No one, it seems, remains of Wulfrun's once powerful Mercian family to trouble him. No one, that is, but twelve-year-old Aelfgifa, and her two blind brothers now dependents in her care.  Replica of the Suontaka sword, by Macdonald Academy of Arms. Replica of the Suontaka sword, by Macdonald Academy of Arms. Anglo-Saxon artists in all forms were fond of playing with images and letters, to suggest additional meanings beyond the obvious. The precise owner of this exquisite sword -- the blade is badly corroded but is believed to have been of the best quality, Ulfbearht type -- was clearly a man or woman of high status. The handgrip is unusually small, only 6.5 centimeters long. Another sword of this type, but with Viking imagery, was found at Suontaka, Finland in a woman's grave. If this sword did indeed originally belong to a woman, who could she have been? Historically, the highest status Anglo-Saxon woman known to have been in Norway at the time was Aelfgifu, handfasted wife of King Knut (Canute) of England, Denmark, and Norway. From 1030 to 1035, she ruled as Regent with their son, Svein, who had been appointed King of Norway by his father. Svein was about 16 at the beginning of his reign. Their rule ended abruptly in 1035 with an uprising of the Norwegian people against foreign domination. The mysterious, yet clearly Christian, symbols on the Langeid sword, as it is known, show a striking affinity with earlier Anglo-Saxon symbols on the coins minted for Queen Cynethryth of Mercia, in central England. At the time, England was not yet united, and Mercia was the most powerful kingdom, ruled jointly by King Offa and his notable Queen. Notable, especially, because Cynethryth was the only queen of the age to have a coin with her name and image on it. The central image on the right hand side (the reverse of the coin) is the stylized "M" for Mercia. The horizontal bar above indicates an abbreviation. On many of King Offa's coins, the "M" is less spiral in shape, more clearly a letter. On Cynethryth's coins, the outer arms of the "M" begin to spiral, with a more extended central point that looks like a nose. Two dots have also been placed within the spiraling arms to suggest eyes. Taken at first glance, one might even see a face. Looking back at the Langeid sword, the hilt also has a stylized spiral on both sides. The spirals clearly resemble eyes, with a horizontal bar at the top that has been integrated into the design, rather like the bar on a pair of glasses, and indications of a "nose" -- created by a bird's tail and a cross, respectively. Above one spiral, the Hand of God reaches down, carrying a cross, and accompanied by the runic "S" for Sigel, the Sun. On both hilt and pommel, the letter "E" predominates, and is oriented to the direction of the spirals. The abbreviations "SR" and "SH" on the pommel are also important in deciphering the possible owner of the sword. Taken together, the "SR" could well stand for the Latin phrase, "Serva Regina," or "[God] Save the Queen," and the "SH" for the Old English title, "Seo Hlafdige," or "Our Lady," by which Anglo-Saxon noble wives were addressed. If so, the identity of the "E" falls into place.

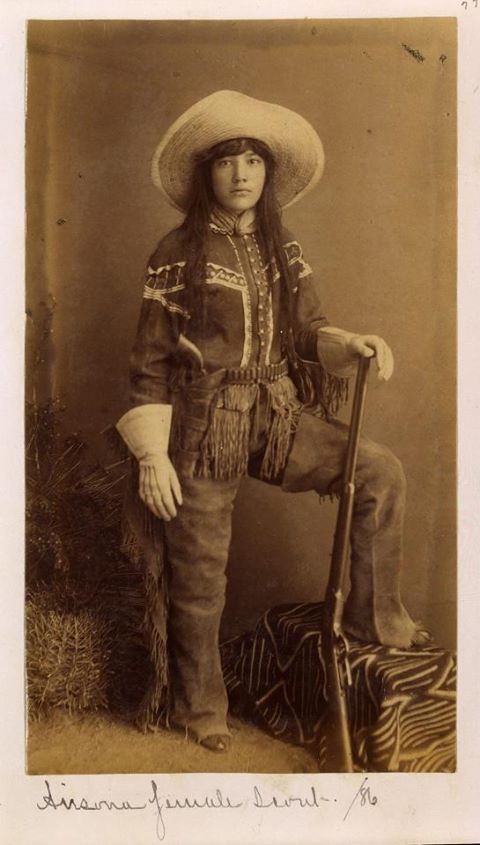

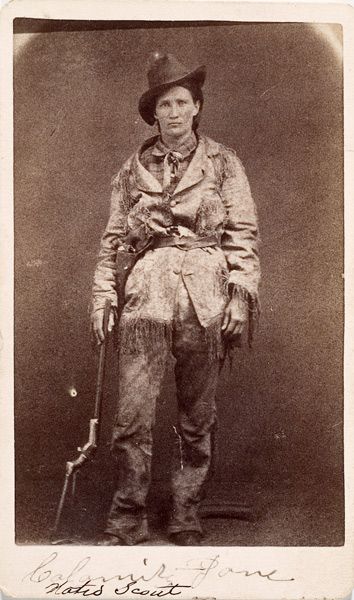

Aelfgifu, the wife of King Knut and later Regent of Norway by his appointment, had her name written as "Elgiva" in Latin. Did the sword belong to Aelfgifu/Elgiva? But what about Emma, the other (more famous) wife of King Knut? It is true that Knut also married the Norman lady, Emma, widow of the previous king, Aethelred. But she was not the slightest bit Anglo-Saxon, and no evidence exists that she was ever in Norway. However, Aelfgifu/Elgiva was descended from a powerful and noble Mercian family -- and, as my next blog will show, had every reason to welcome the Danish prince, Knut, to her shores, and to England's throne. Last edited: February 2, 2019. The caption reads, "Arizona female scout /86." Captivating, and rare, this photo shows a woman dressed as an Army scout with pants, chaps, and rifle. Perhaps she is of Native or Latina ancestry; we are not told. Nor do we know her name. Yet, she must have been a brave person, as very few women dared to dress like men in the 19th century, whatever sort of work they actually did. In The Cowgirl Way: Hats Off to America's Women of the West by Holly George-Warren, the experience of one intrepid Montana cowgirl of the 1880s, Evelyn Cameron, describes the threat she received just for wearing a split skirt, "So great was the prejudice against any divided garment in Montana that a warning was given to me to abstain from riding on the streets of Miles City lest I might be arrested!" Historical photos show women riding the range sidesaddle, roping calves, and even branding stock -- all in long skirts. Not to be held down, however, were the bold women like the scout above and the famous "Calamity Jane," real name Martha Jane Can(n)ary, that defied the restrictive and often impractical dress code of the Old West. Desperation, too, may have played a role in their resistance and their willingness to take the threats, jeers, and sexual harassment that came with "wearing the pants." We know Martha Jane's childhood was tragic, marred by frequent moves led by her father, the death of her mother, and her parents' disreputable lives as a gambler and a prostitute, respectively. When her father also died in 1867, the 14-yr-old Martha loaded her 5 younger siblings into a wagon and moved farther west, to Wyoming. She then took any job she could find, including prostitution, to support her family. In time, the desperate teenage girl grew into a determined and fearless woman. She shifted her work choices to those that were better paid and allowed her some degree of autonomy -- "men's work." For these jobs, she adopted traditionally male dress. But the pain she must have suffered beneath her tough exterior -- pain caused by the aggressive male dominated culture -- led to alcohol addiction. She went through a series of failed relationships and had several children that were placed in various foster homes. Even the exploits she related in her autobiography were often denied by the men who saw them. As "Calamity Jane," she was caricatured into an Amazon of the West, an aberration that could be laughed off and dismissed. Yet it is precisely those qualities of defiance and bravery that have kept her famous long after the men who used, abused, and tried to silence her have died. For all the bold women of the West, it's time we heard them roar.

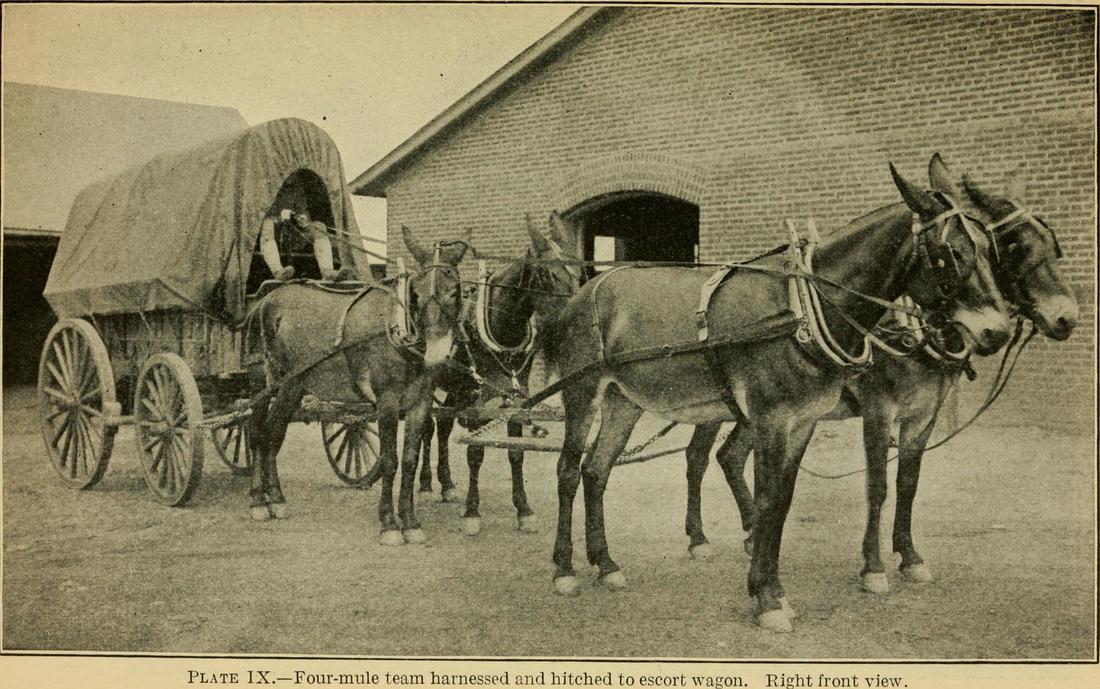

When we think of the pioneer trail, or the stagecoach route, or the Army supply wagon of the Old West, we usually imagine a team of sleek, strong horses trotting along or perhaps the steady plod of oxen. But in the desert Southwest, the humble mule reigned supreme. Twice as fast as oxen over rough ground, and sure-footed like his donkey parent, the mule was the quintessential "horse"power where water was scarce. A mule could pull a load 30 miles a day or more between water stops. Oxen could barely make 15 miles due to their slow pace. Mules also had the donkey's tolerance for heat and cold.

In the California desert between the Colorado River, near present-day Ehrenberg, and the San Gorgonio Pass, gold miners created a roughly 180 mile supply route along an ancient Cahuilla footpath that linked tiny natural oases to rivers and streams. In one section, the distance between water was 35 miles! But this was no obstacle to the prospectors and coach drivers, who dug wells and built stage stops along the way to bring (a little) comfort to what was known as the "Jackass Route" for the hardy mules who pulled the wagons over those dry, dusty miles. Today, the Bradshaw Trail is a 4-wheel-drive road tracing that mule route through the desert.

|

ExploreDig deeper into the worlds in my stories with these links. Archives

November 2022

Categories

All

|